At a newly renovated plant in Riddle, Ore., workers glue together boards harvested from nearby forests, where Douglas fir has grown for thousands of years, and feed the resulting 10-by-30-foot panels into a pneumatic press.

What comes out three hours later, their boss is convinced, is the building material of the future.

Proponents of the material, called cross-laminated timber, or CLT, say it can be used to erect buildings that are just as strong and fire-resistant as those made from steel and concrete. Those qualities have helped excite the passions of architects and environmentalists, who think it could unlock a greener method for housing the world’s growing population, and timber producers, who hope to open a U.S. market for the value-added good.

“We see a horizon that’s very promising out there,” said Valerie Johnson, who with her sister and mother owns D.R. Johnson Wood Innovations. The company employs 125 workers at a traditional sawmill and the laminating plant, which Johnson just expanded by 13,000 square feet to accommodate production of the new material. She’s fielding calls from curious builders and is manufacturing samples so the material can be tested for fire safety and structural soundness. Currently, three North American manufacturers are certified by the Engineered Wood Association to make CLT for the construction of buildings, including D.R. Johnson and two Canadian companies.

“People say this whole thing is six years out, but I’m fighting that,” said Johnson, 63.”There’s no reason to lollygag around.”

Mass timber construction, which uses CLT and other engineered wood products, was pioneered in Europe in the 1990s to replace concrete blocks in the construction of single-family homes and has slowly gained popularity. Wood sequesters carbon from the environment, while producing concrete emits carbon, exacerbating global warming. The system for building with CLT, Johnson adds, involves assembling prefabricated parts, speeding construction, and paring labor costs.

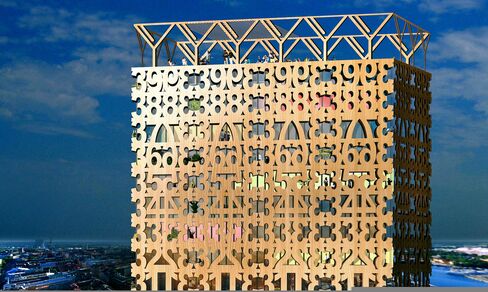

Those attributes have sparked a race to build the world’s tallest wood building. Recently proposed structures include a 100-story tower in London, nicknamed the Splinter, and a 40-story building in Stockholm with a distinctive façade that should be a hit with quants and preschoolers alike:

A vast chasm lies between architectural drawings and completed buildings—to bridge the gap, add bank loans—and there’s a good chance those designs won’t get built. A number of wood buildings in Australia, Norway, and the U.K. have jockeyed for the title of tallest wood building in recent years, all topping 10 stories.

Interest is spreading from Europe to North America. In 2013, Vancouver-based architect Michael Green proselytized for the material in a TED Talk on the subject that’s been viewed more than a million times. The same year, SOM, the Chicago architecture firm that designed the world’s tallest building, published a white paper outlining techniques for building a 42-story wood building. Last year, the U.S. Department of Agriculture awarded a pair of grants to fund work on tall wooden buildings in New York and Portland, Ore.

“On the economic side, the benefit could be tremendous,” said Senator Jeff Merkley, an Oregon Democrat, who plans to co-sponsor a bill introduced in May that would fund further research. CLT could expand the market for timber products from single-family houses to larger buildings, and the process of turning raw boards into mass timber lets companies such as Johnson’s hire more workers.

The next challenge is to persuade building departments across the country to approve buildings made of mass timber. That means proving that the laminated wood panels are fire-resistant and showing that the engineering is sound. Over the longer term, mass timber proponents will have to answer a laundry list of questions, including whether people really want to live and work in tall wood buildings and whether trees used to make the material can be sustainably harvested1.

“It’s going to take some time to build up the infrastructure here to compete with materials already being used,” said Thomas Maness, dean of the College of Forestry at Oregon State University. Eventually, the Pacific Northwest could be home to a half-dozen manufacturers, Maness said.

Still, if mass timber gains traction in the U.S., Johnson, whose parents founded her company in 1951, will be well positioned. For the past 50 years, D.R. Johnson has made glue-laminated beams, industry-speak for what you get when you join two-by-fours into solid columns. The biggest beams the company has made are 9-foot-wide, 140-foot-tall posts custom-built as utility poles used by the fracking industry in North Dakota.

That experience gave the company a head start on producing CLT, though it still needed to hone new techniques and buy new equipment. Johnson invested in a custom-built panel press at the end of 2014 and produced wall and floor panels for its first project, a four-story building that went up in Portland in February. Now the company is installing a robotic fabricating machine to prepare panels for job sites and bidding on new projects.

“If you look at the architecture or engineering or construction industry, there are a few pioneers in every field, and those are the people we’re working with,” Johnson said. “It’s been a once-in-a-career opportunity to be out in front of something.”